“Honorable Turner W. Bell, the greatest Habeas Corpus Lawyer of the West,” proclaimed the Kansas City Sun in an article covering Bell’s defense of three labor union dynamiters. The title would follow him throughout a remarkable 61-year legal career during which he handled more than 1,400 habeas corpus cases. Over the course of his practice, Bell appeared before courts of appeal in eight judicial districts, building a reputation that extended far beyond Kansas.

Turner William Bell was born into slavery on April 1, 1857, in Corinth, Mississippi, according to his death records. He was the second eldest of eleven children who survived to adulthood.

When the Civil War erupted, Corinth became a strategic focal point for both Union and Confederate forces. Two major rail lines intersected in the town’s center—the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, running east and west, and the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, running north and south—making it a crucial transportation hub.

Following the Battle of Corinth, Bell’s father, Peter Bell, gained his freedom. According to the Department of Iowa Grand Army of the Republic, Peter enlisted as a private in the 110th United States Colored Infantry and was mustered out of service in 1865. After the war, the Bell family relocated to Dallas County, Iowa.

They settled on a farm near Adel in a largely Quaker community where young Turner attended school. He excelled academically, graduating with honors from high school and later earning his law degree from Drake University. Bell made history as the first African American to be sworn into the Iowa Bar Association.

There are differing accounts of when Bell joined the Leavenworth County Bar. He first appears in the 1887 Leavenworth City Directory with a law office at 416 Delaware Street. However, several newspaper reports state that Judge William C. Hook swore him into the Leavenworth County Bar in 1886.

In the years that followed, Bell maintained offices at various downtown Leavenworth locations—several of which still stand today. From this professional base, Bell devoted himself to what he once referred to as his “hobby”: securing freedom for those unlawfully imprisoned. It is estimated that he helped free more than 1,500 individuals through writs of habeas corpus. Today, habeas corpus remains a fundamental legal tool used to restore liberty to individuals held in state or federal custody.

By 1915, Bell’s office was located in the prestigious Wulfekuhler Building, where he practiced alongside other attorneys. The city directory of that year lists him as the only “colored” attorney practicing law in Leavenworth.

In 1918, Bell joined the newly organized Kansas Defense Society as legal counsel. The society, formed to “test the constitutional rights of the race along civil, political and other lines that may be necessary to bring about justice and sentiment in behalf of the race in this country,” was reported in the Topeka Plaindealer on November 29, 1918.

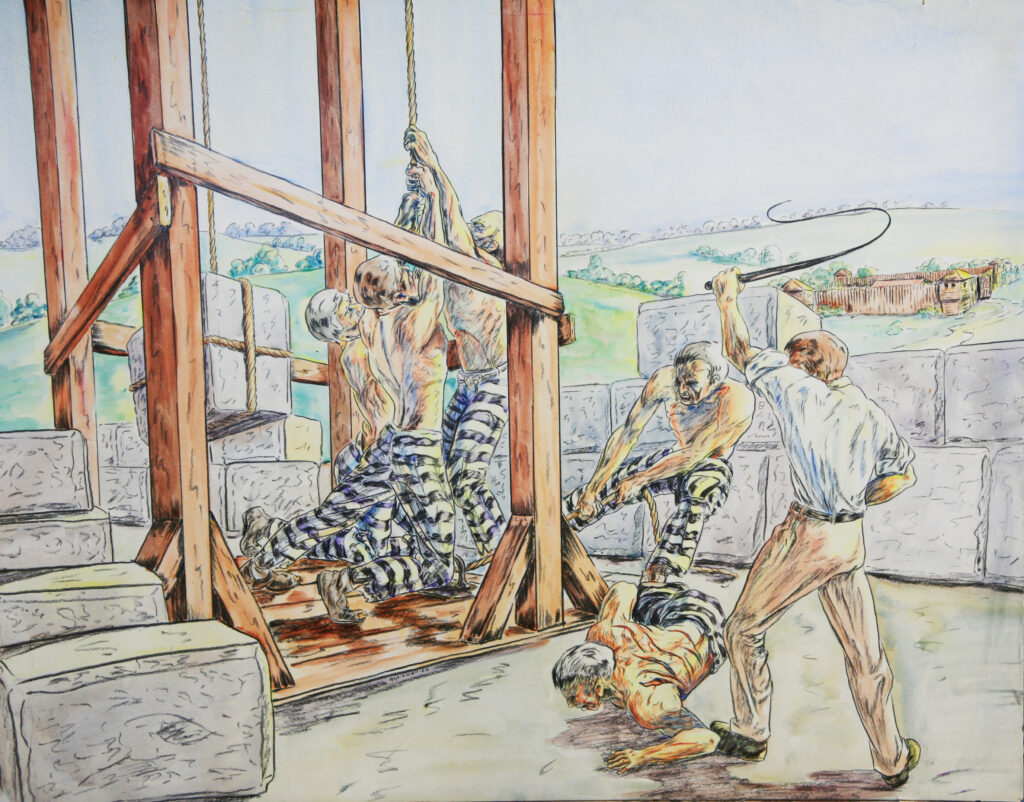

The Kansas Defense Society emerged in response to the court-martial and execution of 19 soldiers from the 24th Infantry following the 1917 Houston Riots. A military court at Fort Sam Houston convicted 118 enlisted men; 63 were sentenced to life imprisonment at the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth. Bell filed a writ of habeas corpus before the United States Supreme Court, arguing that the court-martial proceedings did not comply with established military law and that the men were not performing soldierly duties at the time of the riot, nor was the nation formally at war. His arguments were reported in The Leavenworth Times on May 23, 1920.

Through the combined efforts of Bell and Congressman D.R. Anthony, Jr., of Leavenworth, the life sentences of these men were eventually commuted to terms of ten to fifteen years.

Bell married Elizabeth “Lizzie” Patterson in Leavenworth in January 1890. Lizzie became an active figure in social and political circles. In 1909, she was elected president of the State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and in 1915 she served as a delegate to the Northwestern Federation of States for Colored Women in Chicago. Lizzie’s mother, Martha, lived with the Bells at 744 Kickapoo Street until her death in 1924 at the age of 100. In July 1920, The Leavenworth Times reported that Martha had walked from her home to the Leavenworth County Courthouse to register to vote following passage of the 19th Amendment, then walked home after resting—a powerful testament to civic determination.

Turner W. Bell continued practicing law well into advanced age, eventually becoming the oldest member of the Leavenworth County Bar. He died on August 25, 1948, at the age of 91, leaving behind a legacy defined by justice, constitutional advocacy, and an unwavering commitment to liberty.